The Philosopher's Elevator

How LLMs grant access to every floor, not just the penthouse.

Wilfrid Sellars famously referred to philosophy as “Understanding how things (in the broadest sense of the term) hang together (in the broadest sense of the term).” Said another way, he claimed that philosophy is about properly connecting the frameworks that describe reality at different levels. A “Philosopher”, then, is a person who is specifically skilled at figuring out how all our different frameworks of reality do or don’t connect to each other, and in what specific ways. Their training enables them to shift across the layers of abstraction as needed.

This is what software development has now become.

Years ago, software developers had to think very carefully about how their software used a system’s available memory. Memory was a precious thing, and computers had precious little of it, so using it precisely and efficiently often meant the difference between software that would or wouldn’t work at all. “Memory management” at the program level was an incredibly complicated and finicky task, often requiring hundreds of hours of painstaking notes, reference lookups, and trial and error. Just imagine that, for a while, programs functioned like this:

→ Do operation X and put the result in memory position 0x4F00.

// And then, hundreds of lines later in the program

→ Do operation Y to whatever is in position 0x4F00 and this time store it into 0xB48.

// Then, because memory is precious and you’ll need that slot for something else, you can’t have 0x4F00 just sitting there with stuff on it, so you better:

→ Delete whatever was in 0x4F00.

This forced developers to spend massive amounts of time keeping track of whatever was going on within memory addresses at all times within their programs. Which did make for highly efficient programs, but also meant developers spent a great deal of time worrying about memory addresses rather than the million other problems a software developer could’ve been working on. Compared to today, only a handful of dedicated souls were willing to brave the monotony of this kind of work day in and day out.

Then something fundamental shifted in this realm that would change software development (and developers) forever - that shift was abstraction.

First, developers built programming languages, like C, that would handle the vast majority of the memory allocation work automatically. Meaning you wouldn’t need to devote your valuable time to tracking the exact position of where your data was physically being kept, and you didn’t have to think about where or precisely how your data was physically stored at all; instead, you were free to think at a higher abstraction layer. You could now call <0x4F00> something far easier, and more human, to think about, such as <Bob’s_Paycheck>, and, like magic, <Bob’s_Paycheck> would now just be a thing abstractly stored somewhere and somehow in the system’s memory. You didn’t really know where, but it didn’t matter. Because 0x4F00 was never the point, the point was calculating Bob’s paycheck so accounts payable would know how much Bob should be paid at the end of his shift.

Decades later1, programmers also developed so-called “garbage collectors” that took care of cleaning up your memory allocation spaces when your program was finished using them without you yourself having to write a single line of code specifying how or when this would happen. Today, almost nobody who calls themselves a software developer under 50 even knows what ‘memory registers’ are, let alone needing to concern themselves with such details unless they have an academic interest in them or work in very specialized fields.

Yet, this trend wasn’t without its critics. For years the respectable position was to resist the urge to use these tools that would “abstract away” from what was actually happening under the hood of your program. And these detractors had a point, the early versions of these tools resulted in noticeable performance hits and were buggy and unreliable. “Real programming” meant do it yourself; it meant long sweaty hours in a basement with your notebooks full of address tables.

Eventually though, the bugs were worked out and, as hardware improved, the performance hits became imperceptible for all but the most niche of applications; the holdouts either switched over or aged out of the profession. The costs of abstracting away from memory registers were real, the tradeoffs existed, they were just dwarfed by the perceptual leverage gained from operating at a different level of abstraction - a level more suited to what the program and the programmers were concerned with.

Fast forward to the present day, and if you’ve been paying attention to LLM assisted code development, you might expect LLMs to be the next evolution in the ladder up the abstraction layer. Instead of having to care about the dollar value in <Bob’s_Paycheck>, you’d simply tell the machine “make sure my employees get paid correctly” and never think about the implementation at all. People talk about this all the time - that LLMs are driving us towards the final rung on the top of the ladder, a revolution in abstracting away from the program entirely.

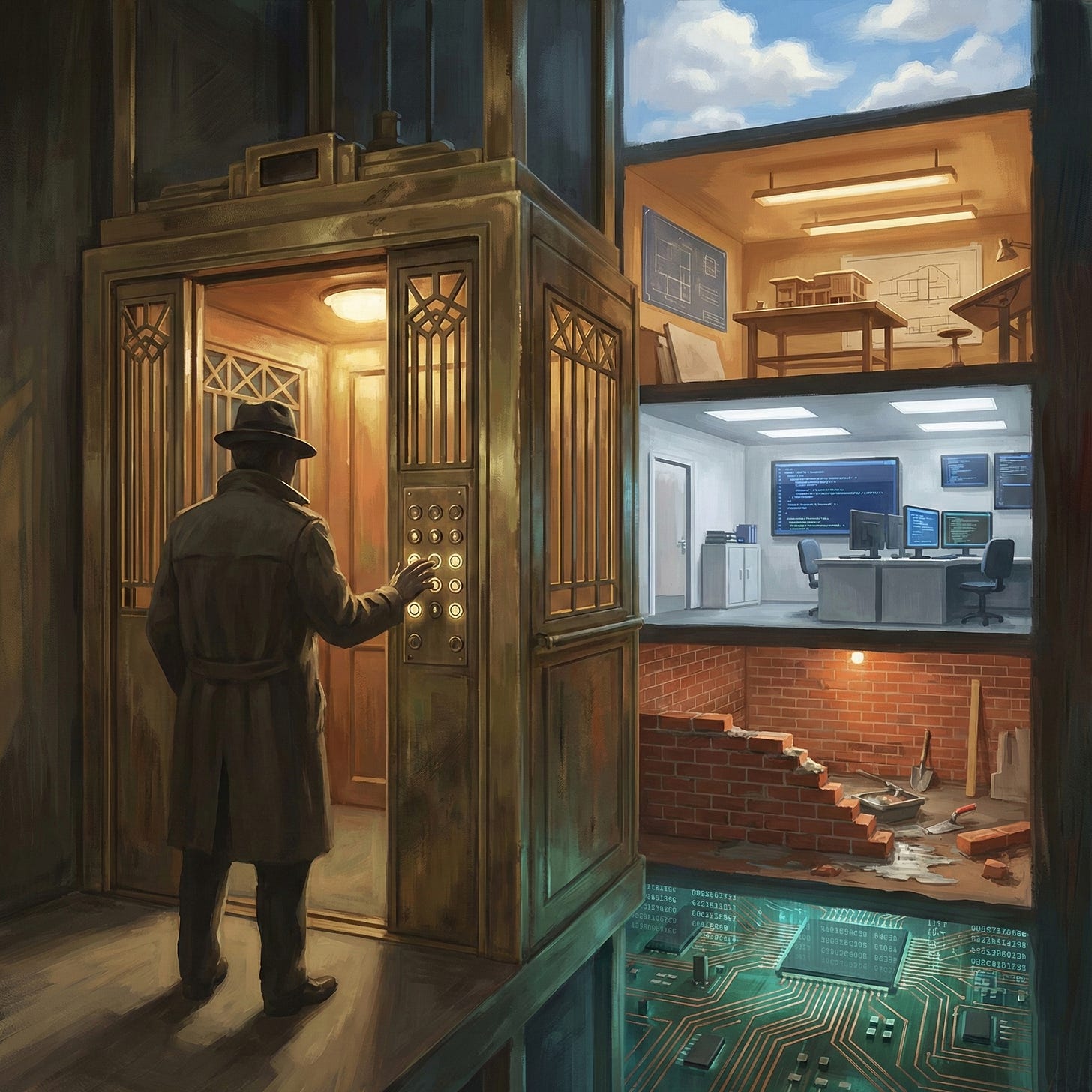

But the power of LLMs isn’t that they allow you to abstract away from the ground truth, it’s that they give you the tools to seamlessly dance between layers of abstraction as you see fit. The LLM isn’t the last rung on a one-way ladder that you climb to the top floor, it’s an elevator that you take to whatever floor of abstraction you should optimally be operating in to do what you want to do. Instead of walking over the gravestones of assembly programmers, we can resurrect and embody them by way of LLM precisely when we need them, giving us incredible power to manipulate things at any and every level as appropriate. The new skill isn’t knowing assembly, C, or even “Hey Claude, build a program”, it’s understanding how and when to switch lanes between these.

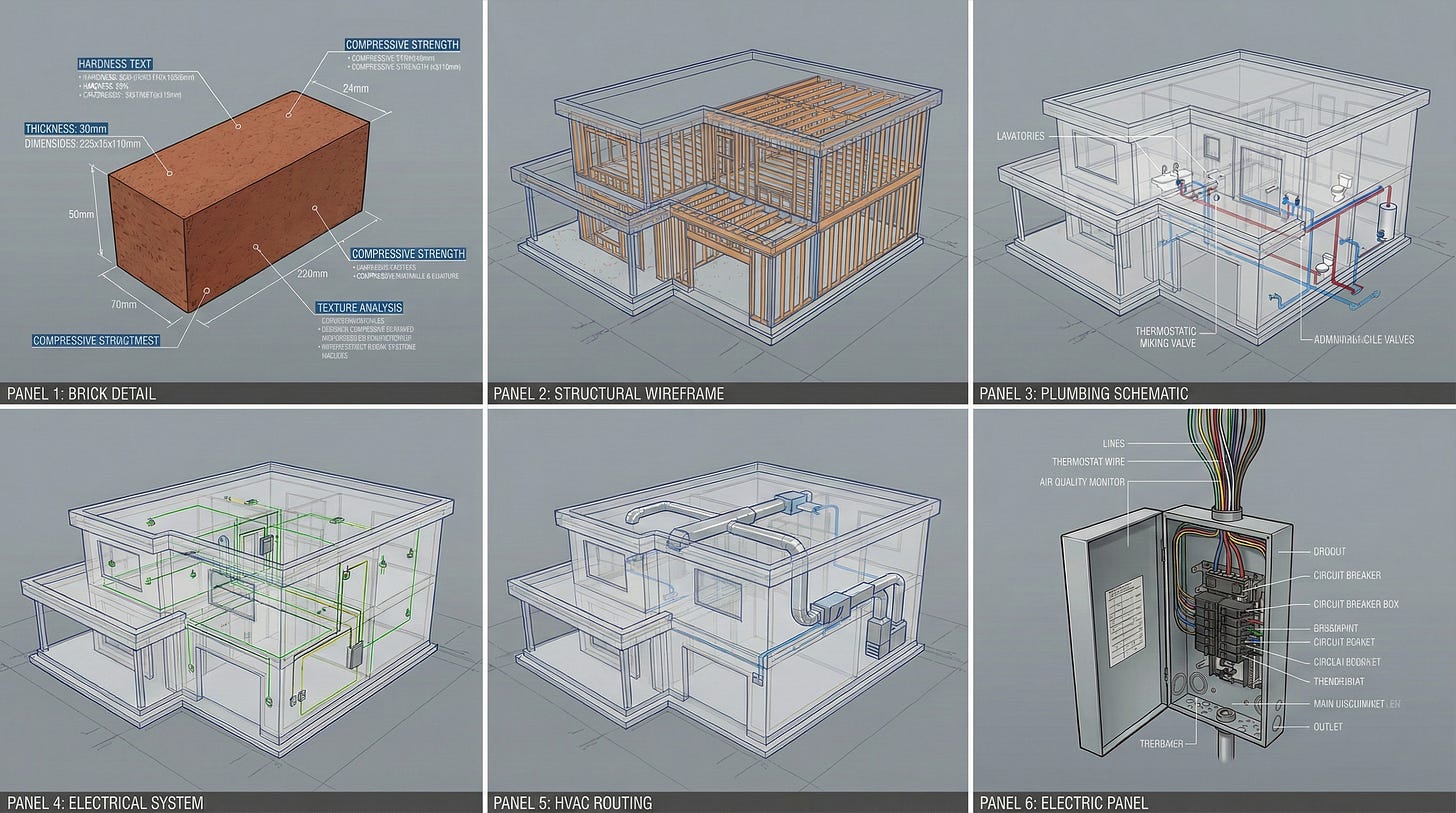

Take the example of building a house. Houses are complicated things. Every level of abstraction requires mastery. You might be good at architecting the house, but you won’t know how to lay the bricks. You might be great at laying bricks, but you won’t have a clue how to wire the electrical system. If the purpose of LLMs was to let you forget about the bricks, if all you had to say was “build a house”, you’d never be able to do anything interesting or important at the brick layer at all, and sometimes the brick layer matters. Sometimes you want those bricks to be better insulated, have higher tensile strength, or perhaps you want to round them along an artistic corner.

As Sellars would say, the philosopher’s skill isn’t mastering any one layer of abstraction; reality is too complicated for that; it’s the judgment to know which level matters right now and how they connect to the others.

That’s the power LLMs give us. Not mastery over any one thing. Not climbing the ladder to the top and never looking back down. No, they turn us into philosophers.

Actually, LISP did it first all the way back in 1958… but like so many of LISP’s great ideas, it was ignored for decades until Java and Python did it.

Max Marty has provided us with some beautiful metaphors, and a reminder of how recent it was that every interaction with a computer was a time-consuming frustrating hassle. Now we have come so far that we can have higher levels of more abstract levels of frustration, FOMO, and real productivity. The interactions we now have with LLMs are truly amazing, and I found this article inspiring. We must embrace modernity and learn to learn with our AIs to create amazing futures together.